Written by Max Muller

You may think our disposition towards having a good reputation and being remembered fondly is the foundation upon which we base our actions. In this article, however, I will argue that this is not necessarily the case. I aim to show that it is not so much the idea of being remembered well that guides us through life, but that we are in actuality more concerned with being remembered. Period.

This can be inferred, in my opinion, by examining the lives and opinions of various historical figures and certain current cultural phenomena. I will try to unravel why being etched into our collective memory is so important to people.

A Lasting Legacy

First, let’s focus on the idea that everyone aims to leave behind a positive legacy. It can be illustrated well with the story of Alfred Nobel. As a precocious chemist and engineer, he invented dynamite in 1867. He patented his invention and made a fortune out of it.

When Alfred was 55 years old, his brother Ludvig Nobel passed away. Due to a misunderstanding, some writers for a French newspaper came to believe it was Alfred Nobel himself who had deceased. Thus they wrote an obituary of him, entitled “The Merchant of Death is Dead.” When he read it, he was appalled by the idea that he would be remembered as an opportunistic salesman of deadly weapons.

After he recovered from the shock of this discovery, he devised a plan to change his reputation. Alfred decided he would donate the majority of his wealth to the Nobel Prize (including, ironically, the peace prize). His legacy is nowadays largely viewed in positive light because of this generous decision.

A Higher Calling

Alfred Nobel was not alone in his aim to leave a positive legacy. Whole religions (with billions of followers) are centered around the idea of behaving well and reaping the benefits after death. In Christianity, for instance, sinners may redeem themselves to be allowed to go to heaven. Likewise, Hindus try to obtain good karma during their current lives in order to reincarnate as a better person in their next lives.

Thus, many people indeed wish to be remembered well, and will try to behave accordingly. They cherish the wish to have had a positive impact on the world. However, not everyone shares this kind of moral compass. Some are driven by other motives.

A Poète Maudit from Leeuwarden

Jan Jacob Slauerhoff (1898 — 1936) was arguably one of the most important Dutch poets of the 20th century. In addition to his literary qualities, he was also a notoriously difficult person. Tragedies and quarrels marked his life. Additionally, he was a womanizer of both married and unmarried women, and was chronically sick.

Towards the end of his life, he wrote his famous poem “In Memoriam Mijzelf” (“in Memoriam Myself”). The last two stanzas are worth quoting at length.

| IN MEMORIAM MIJZELF … Ik laat geen gaven na, Verniel wat ik volbracht; Ik vraag om geen gena, Vloek voor- en nageslacht; Zij liggen waar ik sta, Lachend den dood verwacht. — Ik deins niet voor de grens, Nam afscheid van geen mensch, Toch heb ik nog een wensch, Dat men mij na zal geven: ‘Het goede deed hij slecht, Beleed het kwaad oprecht, Hij stierf in het gevecht, Hij leidde recht en slecht Een onverdraagzaam leven.’ | IN MEMORIAM MYSELF … I leave no last bequest, Smash life’s work at a stroke; No mercy I request, Curse past and future folk; Stand tall where they now rest, And treat death as a joke. — I look fate in the eye, Have said not one goodbye, But want men when I die To say just this of me: ‘He did good very ill, Served bad with honest will, Succumbed while battling still, Undaunted, lived his fill, Intolerant and free.’ |

Slauerhoff had come to the realization that he would probably be remembered as an insufferable person after death. What is interesting in this regard is that he did not seek forgiveness: “No mercy I request.” He did not strive to make one last attempt to redeem himself. He simply admitted he was essentially a villain throughout his life who “served bad with honest will.”

So in Slauerhoff we have found a person who wasn’t driven by the idea of leaving behind a positive legacy. And yet, the man was driven, and left behind a considerable body of literary work.

If he was not interested in leaving behind a good legacy, we could wonder what else drove him in life. In my estimation, the answer is embodied by the poem itself. Although he states that he leaves “no last bequest,” Slauerhoff is lying. The poem does not represent the idea of being remembered well, but of simply being remembered.

Slauerhoff aimed to solidify his legacy by means of his writings. In a sense, his malevolent ways endure through this poem.

Achieving Immortality

“Don’t forget me, I beg.” — Adele (Someone Like You, 2011)

We seek to extend ourselves to the future. As one of the few species that is aware of its own immortality, we aim to combat death by all means necessary. One of those means is having children. Our DNA is thereby passed on to the next generation, allowing us to, in a sense, continue to live on through a new body. Although we all die eventually, our genes are safeguarded this way.

However, the biological continuation of our being is not the only method through which we can “survive.” There are other ways to live on after we die. One of those is continuing on in the minds of others.

Ever since the invention of writing, human beings have had the unique capacity to precisely transmit vast amounts of complex information to future generations. Our values, fantasies, and even identities can be recorded efficiently for posteriority. Every writer seeks to endure through his or her literary creations. They extend and preserve a part of themselves through their writings.

Photo: Jonas Guigonnat

A Common Desire

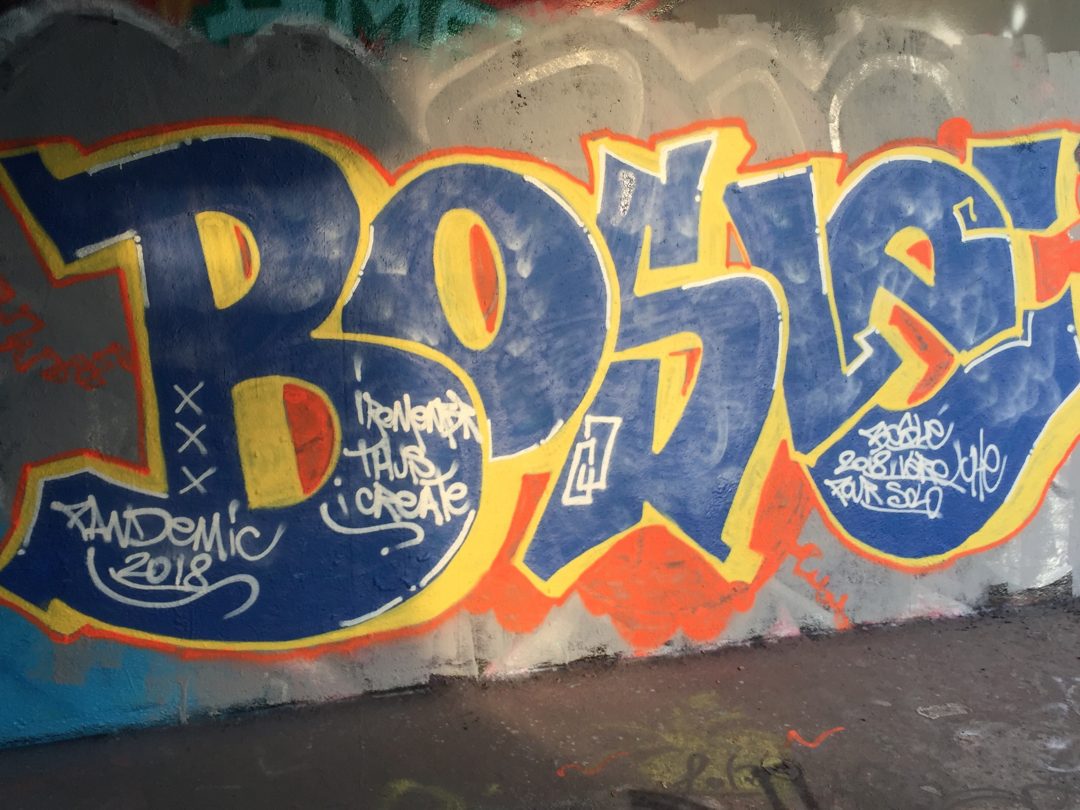

It’s not just writers who seek to be remembered. The desire for endurance is arguably the most primal drive of all creative endeavors. Scientists hope their theories replace the old ones and that they are forever acknowledged for their discoveries. Rulers demand the erection of statues and other monuments as a solidified sign of their dominance. Graffiti artists leave their mark on walls to pay an enduring homage to themselves and their ideas.

The will to be remembered is not even restricted to those with creative or coercive powers. Everyone seeks to endure in the minds of others to a certain degree…most of us shiver at the prospect of being forgotten.

In Hannah Arendt’s treatment “On the Nature of Totalitarianism: An Essay in Understanding” she mentions that some tyrants acknowledged the terror of being discarded by history, and utilized it themselves. For instance, prisons under despotic rulers were often called places of oblivion and at times forbid the family and friends of a convict from even mentioning his or her name – to the extent that they could even be punished for breaking this rule.

Now that the possibility of materializing memories of oneself has become democratized, the fear of being forgotten has become more visible. Many immortalize even the most remotely interesting events of their lives with pictures on Instagram or bite-sized stories on Twitter. Furthermore, in the early 1990s, the memoirs written by “ordinary” people experienced an upsurge. Even more recently, people have started frantically tracing their heritage with DNA ancestry tests, such as 23andme. People wish to pass down their own heritage and legacy due to a fear of being forgotten amid a society filled with technological advances and increasingly rapid development. At the same time, these tools aid people in finding their place in a confusing, fast-changing world.

Thus it seems there is a one-to-one correspondence between our desire to be remembered, and the preservation and extension of ourselves in various forms. It is connected to the idea of making an impact on the world. We wish to to make a dent in the universe, a mark that will forever be connected to ourselves. It’s not just a dent, it’s our dent.