Dear Infected,

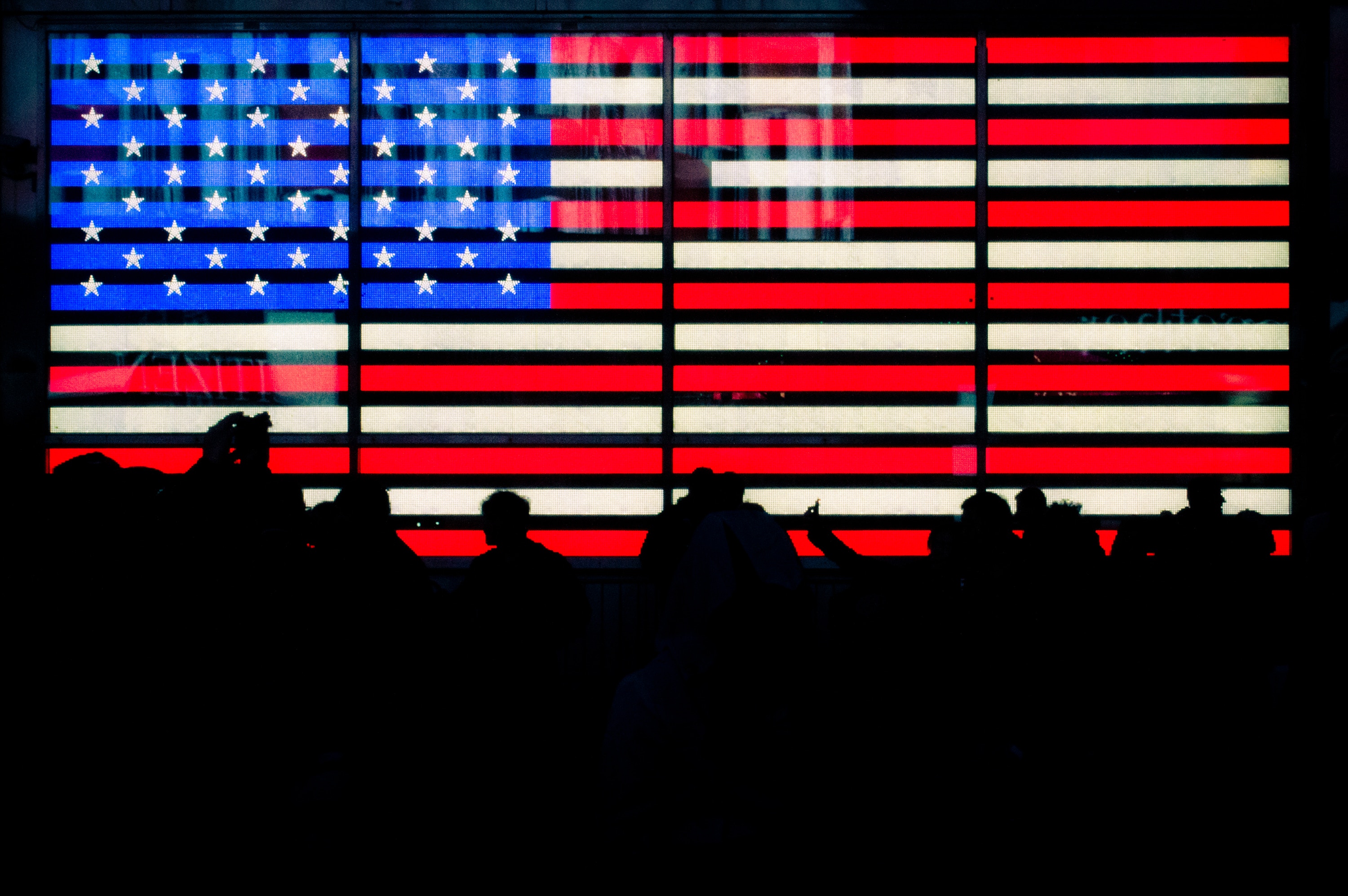

For better or worse, the last couple of years have been an exciting time for politics. From Brexit, to the election of the 45th US President, to a string of referendums for independence, people who might otherwise have ignored the political cycle have been forced to care. The threat of blatant corruption may discourage some from taking part, but passivity doesn’t incite change. For March 2018 Pandemic would like to give voice to the ideas you can’t share at the dinner table with the theme Political Utopias.

With the way media works, the loudest and most controversial voices tend to be amplified above all others. But we know that these voices of decisiveness and hate are not the only ones out there, and that a divided world is not the only alternative to the world we live in now. Theirs is a vision of utopia derived from the Greek οὐ (“not”), meaning “no-place”. We’ve experienced their vision of the world in extremes, with human slavery, the oppression of women, and the holocaust. It’s not a place we should go back to.

This month’s theme uses the utopia derived from the Greek εὖ (“good”) to mean “good place” which we are closer to now than at any other point in human history. When the voices of repression grew loud, the voices of the repressed grew louder. We cannot let the wave of progress seen in the #Metoo movement, or March For Our Lives, lose momentum. Nor should we think that the fight is over once a few goals are achieved. History has shown that there is always a new instance of injustice waiting to crop up, so those seeking justice must be ever vigilant.

To help start the discussion we’re launching the issue with four articles representing the authors’ personal visions for how the world could, and maybe should, be changed. No article contains a design for shaping the whole world at once, but each one can be considered a piece of the puzzle we’re trying to build together.

Hopefully reading these articles inspires you to write your own, and join this issue’s debate.

We look forward to hearing from you!