Written by Floris van Dijk

I don’t think Schopenhauer was right in saying that desire is the source of all pain. Human ambition is not necessarily harmful. It just needs to be filtered to bring out the good, and avoid the evil.

Ambition can take countless distinct forms, but it has never been a major concern to conceptualize them. Historically, all forms were encompassed by the term ambition. In Latin, ‘ambitio’ is derived from the verb ‘ambire’, to strive. Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics claimed that there was no word in Greek that unambiguously represented the virtuous intensity of ambition. This lack of conceptual clarity perpetuated for centuries, as it remains vague usage that we know today.

The establishment of the feudal system in Europe was paired with a general critique of ambition. Ambition was taboo because human agency bred an impulse at odds with the infallibility of the natural order, the will of heaven. At a time in which identity and rank were determined by birth, ‘reaching for the stars’ was deemed immoral.

Even as late as 17th century France, ambition was defined as the “unruly passion for glory and fortune”, in contrast to piously seeking the reward of admission to heaven. The ideal citizen was eager to perfect subservience to the king and church.

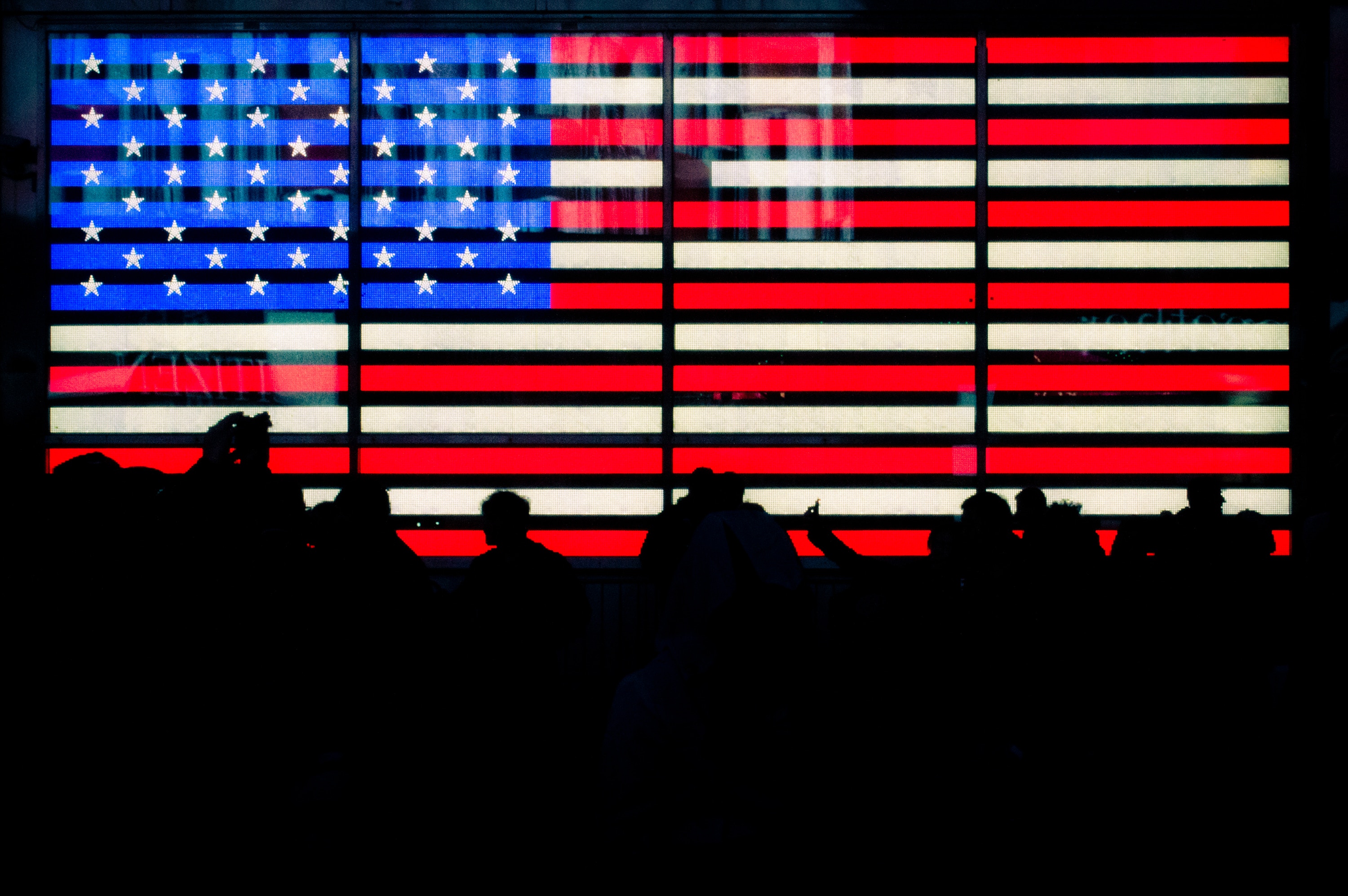

This distinction, however, held only as long as clerics held the supreme power. The French Revolution, American Independence, and the victory of British free trade principles all gave way to a more liberal turn by the end of the 18th century. This brought the possibility of a larger part of the population claiming political and economic opportunities, and was accompanied by the redemption of ambition in language and literature.

As early as 1815, Benjamin Constant was one of many who believed that “ambition is compatible with a thousand generous qualities.” Today, the word ambition as a whole has a positive connotation across languages and cultures: most universities select ambitious students, recruiters search for ambitious applicants, parents want ambitious children.

Nevertheless, unanimity on the value of ambition has not been reached. Philosophy of the arts and architecture-professor Yehuda Safran wrote that “to have no ambition is perhaps the highest ideal.” The reasoning behind her belief is understandable: beyond the personal gains that the tranquility of the ambition-free mindset brings to an individual, the rejection of ambition can be considered beneficial to society, in that it dissolves a fundamental cause of systemic instability.

Photo by Faustin Tuyambaze

When looking at democratic political practice, ambition is indeed dangerous; it was the ambition of individual men that brought down the Republics of Rome, and Weimar. It was the ambition of individual politicians that caused the fragmentation of political parties in the French National Assembly during the interbellum, which caused years of governmental instability and ineffectiveness. It was the ambition of individual warlords, trying to reinforce their personal influence, that explains the death toll of 40 million during the Three Kingdoms period in China.

Ambition is a cause for political coups, a cause for rebellion, a cause for war. Thus, a world without ambition would be a utopia less likely to experience these threats. Yet, if humanity wasn’t moved by the powerful forces of hope, desire, and aspiration, what would the world look like?

It is unthinkable to achieve goals without ambition. So what we ought to do is not to indiscriminately suppress ambition as Schopenhauer would’ve advised, but treat the topic with a little more nuance.

Naturally, extreme forms of ambition can be destructive. This is common sense, but as I perceive it, ambition can have three different outcomes: preservation, creation, or appropriation. There are different expressions of ambition with different psychological and behavioral manifestations; respectively, the ambition to cultivate, the ambition to build, and the ambition to conquer.

The ambition to cultivate aims at preserving a capacity or skill; like keeping a particular ability strong, or maintaining an impeccable backyard. It’s best represented by the example of an athlete: he runs in order to maintain his health and to ensure his fitness over 20 years. Another intuitive example is the practice of a language, done with the sole goal of staying proficient. Not with the underlying goal of applying in the future for one specific job, but for the cultivation of personal knowledge.

The ambition to build seeks creation. It’s the motivation of the architect drawing up blueprints for an opera house with an incredibly imaginative design. In a way, it’s what causes the academic to forget himself in order to focus fully on his study of a subfield for 50 years, in order to contribute to the elaboration or refutation of theories. And of course, it belongs to the emotional core of artists, businessmen, and city mayors.

The ambition to conquer is, without doubt, the most spectacular. It’s this ambition that fuelled the establishment of the great ancient empires, the subjugation of almost the whole world by the European sea powers, and finally the initiation of the Imperialist and Fascist world wars. Essentially, the ambition to conquer seeks appropriation, colonization, annihilation. History books are full of it; many wars were directed by just a few men seeking prestige, while some were started by a nation seeking status. Such ambition is often presented in epics as both glorious and heroic, particularly those actions fueled by a desire for revenge.

Of course, actions are rarely motivated by only one of these forms of ambition. Hybrids of diverging intensities of one form or the others are the rule rather than the exception. Though the most common critique of ambition as a whole concerns this third kind. In a utopia, this form of ambition should no longer exist. It is simply too dangerous.

Most notably, the high-powered nature of the ambition to conquer is destructive at its core. A striking example is Paraguayan President Francisco Solano López. One of the major causes, if not the main cause, of the deadliest South American war was this man’s ambition. It led his small, technologically-inferior nation of half a million into an unwinnable war against an alliance with a combined population of 11 million. This “war of the Triple Alliance” led the Paraguayan population to be cut from 525,000 to 221,000, of which only 28,000 were men. The ambition to conquer has put unbearable sufferings on people across time and space.

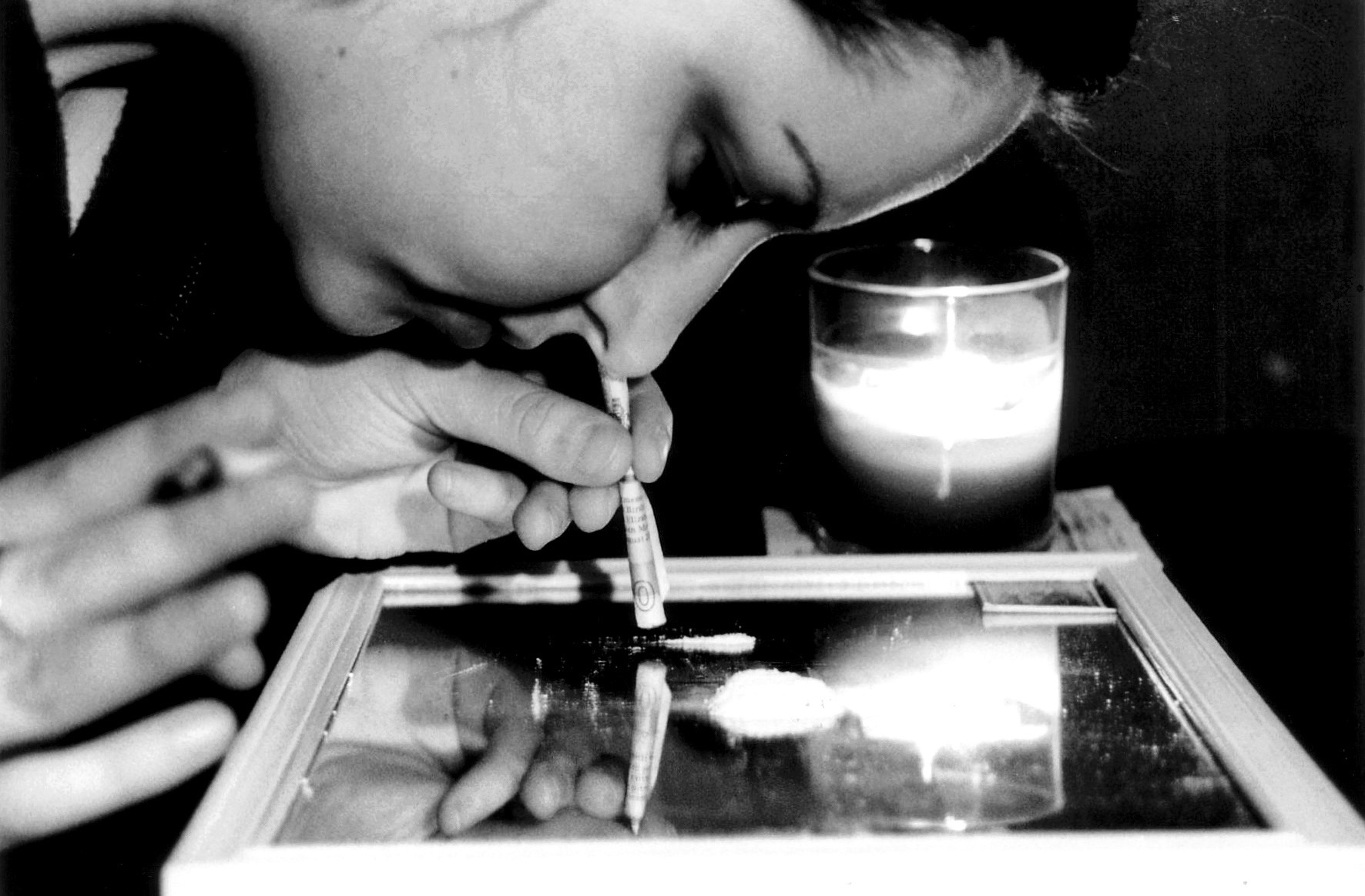

Photo by Danka Peter

Numerous victories aren’t satisfactory for the conqueror, either. Success only feeds this ambition, creating a bottomless abyss, a self-produced addiction. After beating one enemy, you can’t wait to face the next. Pyrrhus couldn’t be satisfied by becoming king of Epirus; he next invaded southern Italy, and then Sicily, and then Macedon, and then the Peloponnese. Each new campaign meant the loss of prior winnings, and eventually the loss of everything else (including his life). Alexander the Great’s empire stretched from Macedonia all the way to Persia for a few years until it crumbled because he just couldn’t get enough. The leader trapped in the vicious circle of conquest resembles Sisyphus trying to roll a boulder up a hill.

A final warning, the ambition to conquer inevitably affects the individual’s relation to others. It’s the suspicion that friends stand in your path to success so you must drop those friendships holding you back from your potential. After all, as French surrealist and poet Phillipe Soupault said “the main enemy of friendship is ambition”. Famously, former French prime minister Edouard Balladur betrayed his close friend the former president Jacques Chirac, as he stood in his way in the race for the presidency. Examples of self-destructing ambition are numerous throughout history. Again, reference should be made to Alexander the Great. Not only did he lose the loyalty of the exhausted soldiers whom he fought alongside for a decade, but he also killed one of his dearest companions, Cleitus the Black. Supportive relationships can never be more than a means to an end for the conquest-driven soul.

Discussing ambition “in its essence” is impossible, since the word doesn’t have one single essence. Ambition is a neutral term, but we should not uncritically support all forms of ambition. We should hold on to our desire to build or cultivate while limiting our drive to conquer. To build the ideal society, humanity doesn’t have to abandon part of what makes it human, but instead learn to avoid the unsustainable and destructive form of the ambition conquer.