Written by Chloé Gregg, Staff Writer

Car horns and bicycle bells echo outside the tall beige walls surrounding the Wisteria Lane-inspired houses of the compound. Absorbed in a game of spies – which involves a lot of pranks on the guards surveying the residence. At times when the air is especially hot and sticky from the exhaust of engines, she notices the stomach-churning odor coming from the river. Like rotten eggs. Having lost track of time, she’s suddenly called by her mother to jump into the lime-green taxi waiting in front of the house.

“We’re going into the city today, remember?”

The city. Behind the pale compound walls she’d forgotten about the chaos outside. There were millions of people living out there, mostly crammed into tiny damp rooms among decrepit blocks of cement. Everywhere in the city, people had built walls.

The other morning as she crossed the impeccable green lawn that cushioned her house, and saw two neighbors walk out from separate homes, dressed in strict-looking black suits. They each stood silently on the edge of the pavement as they waited for their separate chauffeurs to arrive and take them off to work. Avoiding eye contact, they took a discrete look over the small patch of grass that divided them, then glanced back at their watch as quickly as possible. They never uttered a word. It seemed so strange because she knew their children, they were good friends. Most of the kids would meet up every afternoon after school and play hours upon end in the common gardens until dusk. The adults, however, always seemed in a hurry, eager to hide away once again behind those walls.

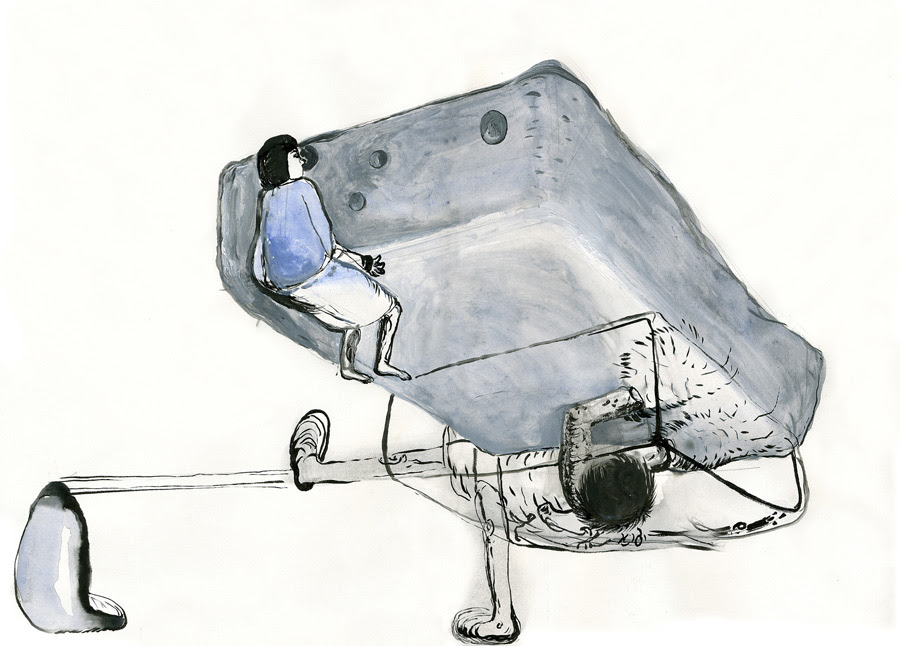

A lot of the things she saw made her fear the city. It seemed like a daunting and lonely place. Whenever she went with her mum to the markets, she’d see homeless people kneeling down, eyes closed, a handout, asking for some coins. People kept passing, treading on their blankets and shooting left-over cigarette buds directly at them. Afraid, but curious, she’d sometimes let her eyes linger on a missing limb or a strange deformation. It sent shivers down her spine. Yet, these images appeared to disturb no one else. Once again, it seemed as if people had placed walls, right there, in between each other, like masks of false reality.

Aside from a few parks, the city rose over her head like a giant concrete mass. Glimmering new skyscrapers popped out from the ground nearly every day and stole a little more of the sky. She’d only ever known it in one shade, gray. She remembered the last time she’d gone to visit her grandparents in the country. Her parents had told her to breathe in all the fresh air she possibly could to cleanse her lungs from urban fumes. She remembered the vibrant colors of the vegetable patch and the salty smell of seaweed on the beach. In the country, her grandpa would often take her to see the cows at the nearby farm. The neighbors lived so far away from each other, yet they all knew when she was back in town. People stopped her at the bakery to ask for news and smiled at every person they crossed when walking.

Back in the city, she never met a familiar face. There were so many people in the streets, walking side by side, yet they never seemed anything more than perfect strangers.

As she grew older behind those compound walls, she began to see the city in a different light. As a weekend escape in the city before exams left its mark. She slid through the metro’s doors and collapsed onto the closest seat, she felt the drain in her body and the thin mask of urban dust that had accumulated on her face. Not daring to cross anyone’s eyes, she sat staring blankly at the window’s safety warning sign. She shifted her gaze to find a new point to stare at, settling on a young man hoping onto the carriage with a guitar.

Walking from the station towards her house, she felt a sting in her chest thinking about leaving the city again. She realized now what it meant to her.

She liked the furor in the streets, the neon lights flashing faces that scurried by. She liked the thrill, the rush, the endless opportunities. Feeling limitless, the city was a drug that kept her going until dawn where she’d see emerging signs of life. Wondering what all these strangers were doing, in which bed had they spent the night? The fantastic cluster of all these parallel lives. She liked that feeling of alienness amongst the crowd. The unpredictable fate they all shared in isolation with one another.

She knew the city could be a lonely place, but seldom gave herself the time to think about it. The walls kept her in comfortable isolation. The perpetual circus of distractions kept her lonely thoughts at bay.